If your case or potential case has video, audio, or still image evidence, you want to be sure to fully understand the digital file and it’s content, from its technical origins to all visual and audible details. You also must organize and prepare information for trial so that the details you have uncovered are something a jury can easily digest. To do this correctly requires 1) the enhancement of the evidence, 2) analysis including reports and charts, and 3) proper preparation for playing the visual and sound evidence in court. For more on audio enhancement, see our page on audio forensics.

Today there are many interesting tools and techniques for taking a closer look at video evidence and for cleaning up sound files to reveal certain sounds or conversations. Keeping track of the details found in all this evidence and discovery is possible through techniques including charts, annotated transcripts, 3D satellite maps, and metadata analysis, to name a few.

If your evidence is from a surveillance camera, it is not only crucial to preserve an exact copy of the original video, but also to document the camera make and model, the specifics of the camera lens, and the camera settings and software system version. In addition, you should create a map that shows where cameras are attached and what direction they face. All these details could be crucial to your case.

When the camera is connected to a digital video recorder (DVR), a network video recorder (NVR), or to a third party cloud system such as Nest (which previously was DropCam), preserve the settings of those recording devices and software versions. The file type of the digital media — how the video or audio was saved and compressed into a file — can help to determine if the evidence might be an exact copy of the original evidence or if it has been edited or altered in some way.

Details, details, details! As the saying goes, the divine is in the details. An expert properly and carefully watching your evidence — or listening to it in the case of audio — can reveal details that you didn’t realize were there. Repeated review is crucial on every major case that comes into our lab, whether it’s a criminal case or a civil case, and whether it’s audio, video, or still images. Attorneys who have worked with us in more than one case know of the importance of giving media evidence proper attention, and all the new attorneys who come to us learn it eventually. Creating clear charts for the attorneys can be very helpful in these situations. We have had many trials where our charts have been used by attorneys to help them respond when inaccurate claims were made by the other side. Watching and listening to evidence until it is remembered and understood in the same way a surgeon must know his tools. If you want to be prepared for court, it’s not a luxury; it’s a necessity.

The results of forensic enhancement and analysis — no matter how complicated and technically involved — need to be explained simply and clearly to a judge and jury. Whether it is explaining how audio enhancement was accomplished or presenting the expert opinion of a transcript detailing what is heard on the sound, or whether it is explaining the technical nuances of a security camera system, if the jury is confused by expert witness testimony, they might think you are trying to trick them.

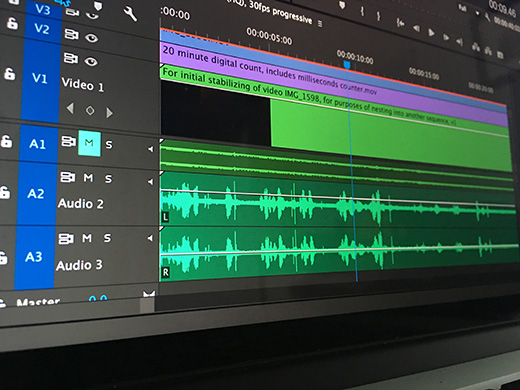

And if your explanation takes too long on the stand, the jury may simply tune out, fall asleep, or be unable to focus on your line of reasoning. When testifying about video, audio, or still image evidence, an expert witness should play the role of a teacher and take the jury step by step, from the receipt of the original evidence to the determination of final results. This requires not only a concise explanation, but also excellent technology for evidence playback.

Along side the expert witness, and often just as important, is the proper setup and presentation of the digital media in the courtroom. Clarity of audio playback allows the jury and judge to hear the sound in the same way the expert hears it. High quality, big screen TV displays will allow accurate enlargements to be seen by the jury without straining their eyes and without depending on the expert witness. The goal is for the jury to see it and hear it with their own eyes and ears.

Do not depend on the court to provide such technology; quite often courts have antiquated projection screens or speakers built into the ceiling, with wiring that breaks unexpectedly or with technicians that aren’t qualified. Courts sometimes own a few higher quality portable TV systems, but those need to be shared among all the courtrooms in the building, so they may not be able to provide one to your case. In addition, with projection systems, the lights in the room or the sunlight coming through a side window will obscure the projector’s light, meaning that details of your evidence can get lost. What is the solution? Setup a large, flat screen television and connect your computer directly to that screen.

The best playback technology will not help if what you are playing is an inferior exhibit. Your exhibits, whether the original source was audio or video or still photos, must tell a simple story and show the results in a straightforward way. Your exhibit should be free of all extraneous details — focus on what is important to your case.

Timelines can sometimes help, as do charts that list events and times where the action is found in the evidence.

Every case and each piece of digital evidence requires a unique approach, so the expert must be flexible, creative, and smart when considering the right method for organizing the evidence into a clear story.